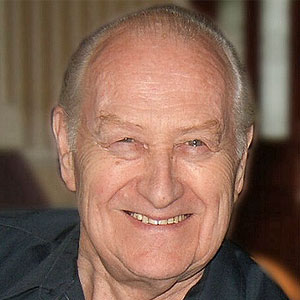

| In Memoriam: Mario Martello April 3, 1924 — October 2, 2006 |

|

| The luthier community lost a valuable resource with the passing of José Mario Martello. Mario, as everyone called him, was more than just a guitar repairman, although that was his primary trade for over half a century. Along the way, he built both classical and jazz (archtop) guitars, lutes, and made major components and modifications to banjos, mandolins, basses, and just about every wooden instrument that wore strings. Born in northern Italy in 1924, Mario immigrated to Argentina with his parents when still a young boy. His father, Giuseppe, was a cabinetmaker, and while still in his teens Mario became familiar with fine woodworking from both the handcraft and the production vantage points. But an interest in jazz led him beyond furniture, and he apprenticed with a guitar maker making jazz guitars. Once married and a father, however, the uncertain political and economic climate in Argentina drove Mario to relocate to New York City in 1957, and, two years later, he tried the opposite coast and landed in San Francisco, where he quickly found work in a large furniture factory. When a coworker expressed an interest in building a guitar, Mario volunteered to help, which brought him to the Satterlee & Chapin guitar shop in the heart of the city. Mario’s timing couldn’t have been better, for San Francisco was the West Coast’s focal point for the folk music revival. Virtually every known soloist and folk group filed through the many coffeehouses and nightclubs in and around North Beach. San Francisco was also home to a thriving jazz scene, including traditional jazz, and both flamenco and classical guitar were popular as well. Once Harmon Satterlee became aware of Mario’s skill and ingenuity, he was given a full time job as a repairman. Mario was called upon to repair and customize a wide range of instruments for amateurs, touring professionals, and everyone in between. Dave Guard’s Vega banjo and Segovia’s Ramírez guitar might cross Mario’s workbench in a single day, along with the Harmony Sovereign of the local Woody Guthrie wannabe. This was long before the publication of any how-to books on instrument repair, or a helpful organization like GAL. Mario had to rely on his skills in fine woodworking, but even more important was his ability to trouble-shoot almost any problem and improvise a solution. It was this combination of talents that brought him to the attention of Jon Lundberg, who had opened a fretted instruments shop across the bay in Berkeley. Soon Mario was able to buy a home in the East Bay, turning the garage into a workshop and making weekly pickup and delivery runs to Lundbergs and a few other music stores as well. Although more involved restorations or customizations might take a month or more, most repairs were returned a week after he picked them up, and both the variety and volume of work he performed was staggering. Jon Lundberg was the leading source of vintage acoustic instruments on the West Coast in the 1960s, and in the days before the mania for originality set in, Jon had Mario customize or modify many instruments. A new D-28 would be given an extended headstock to become a 12-string, while a huge Larson Brothers archtop, for which there was no demand at all at the time, would get a new flat top and become a Super Jumbo that made a Gibson J-200 look puny. Lundberg’s shop had other repairmen, but Mario’s wide-ranging talents made it possible for the shop to restore everything from antique Irish harps to Italian lutes. Mario was typical of many fine craftsmen of his generation in that most of time he was content to work behind the scenes, often seeing others get credit for work he had performed. Although he was featured in local newspapers in Contra Costa County, he never received national attention despite his numerous restorations of guitars owned by famous players such as Segovia and David Crosby. But among those of us who knew him, Mario was always impressive. He was tall and handsome, with effortless and genuine Latin charm. Mario remained active until the last few months before his death, playing bass in a jazz group as he had for years, and fixing instruments for many of the same dealers, musicians, and collectors for whom he’d worked for decades. He gave each repair job the same priority, and never put off completing a task. When he ceased working early in 2006 because of ill health, there were no unfinished jobs and no need for outside help to clean the slate. His diligence and inventive spirit should inspire us all. — Richard Johnston |

Top of Page |