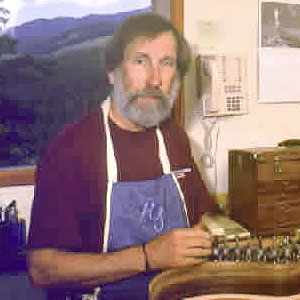

| In Memoriam: Richard L. Schneider March 5, 1936 — January 31, 1997 |

|

| We were all shocked and deeply saddened at the loss of our good friend and colleague, Maestro Richard Lawrence Schneider. He died unexpectedly in the early hours of Friday, January, 31, 1997. He is survived by his brother, Donald Schneider, his sisters, Theodora Schneider-Polla, Janice Allen, and Rev. Karen Thompson, and his daughter Anne Dwyer. Although we have lost a great man, we will continue the work he was so dedicated to... the future of the guitar. — Jay T. Hargreaves I first met Richard in 1964 while accompanying a long-time friend on a chance visit to his Detroit workshop. The three of us spent an enjoyable afternoon taking turns playing his guitars, and I fondly remember Richard's Mexican folk songs. That afternoon changed my life. My friend left knowing he would have a new guitar, and I left knowing I had to make them. Fate smiled and eventually Richard accepted me as an apprentice, fulfilling my dreams. Many months later Richard began my friend's guitar. One day Richard asked if I'd like to work on it. I was surprised and delighted with the prospect of contributing to the realization of my friend's instrument. This thoughtful gesture is typical of the generosity, trust, consideration, and a sense of the poetic that was Richard's. I was the first of many who Richard taught over his thirty-five years of guitar making. He was a great teacher, and his enthusiasm was infectious and inspiring. His work exemplified his standard of fine craft and aesthetic harmony combined with imagination and the eternal search for the ideal sound. He was one of the most innovative people I have ever known, and his contribution to guitar making will continue to influence generation after generation of luthiers. Via con Dios, Richard, you will be missed. Abrazos, — Jeff Elliott A fiery vision burned brightly in Richard Schneider, illuminating the hands of guitarists and the minds of young guitar makers around the world. Our world was diminished by his passing. Last August at the Healdsburg Guitar Makers Festival I went out to dinner with Richard one evening to talk shop. We talked for hours about what were to me were invisible and tentative theoretical constructs of the inner workings of the guitar and the musician's ear, among other subjects. For Richard these things were by no means invisible or tentative. They were as clear and palpable as the fruit on the table between us. Why couldn't people see these things? They were so obvious! Why didn't people pay attention? How would he ever get the world to take notice? Better guitars could be made! Next to Richard Schneider's instruments, traditionally designed guitars look vaguely flat, and even primitive. Richard's instruments served as exquisitely crafted interfaces connecting multiple worlds - the physical world of forest woods and the master craftsman's shop, the scientific world of Dr. Michael Kasha, the spiritual musical world of the guitarist, and the Richard's own turbulent inner world. Learning guitar making from a Mexican master, Richard Schneider was a link in an unbroken lineage of sorcerers/craftsmen stretching back deep into human prehistory, when young men learned the secrets of fire-making and blade-craft to assure perpetuation of the human spirit and well-being of the clan. For Richard, the sacred fire involved illuminating the human soul with music from strings and wood. The musician's ability to penetrate the spiritual world demanded instruments imbued with both power and subtle tonality, a transfigured blade of old — strong, balanced and so very sharp along the edge. Scorning the secretiveness and self-involvement of luthier Prima Donnas, Richard was a wide-open teacher, designing and building instruments as open books for anyone to see and learn. I ran into Richard Schneider one last time at the show in Anaheim, and the fire was burning brighter than ever. Since our dinner at Healdsburg four months earlier, his work had received wide recognition in the international press due to a reporter from the London Economist who had been sitting in the audience at his lecture at Healdsburg the day after our dinner. Richard was exuberant, eyes flashing and smiling. Things were finally looking up. He was making plans for a new shop, and was being pursued by dozens of serious customers wanting instruments. Most importantly, he had fallen madly in love with a beautiful woman who wrote equally beautiful poetry, some of which, of course, he had to show me, and it was beautiful. Rest now, Maestro. We have our work to do. — Tim White |

Top of Page |